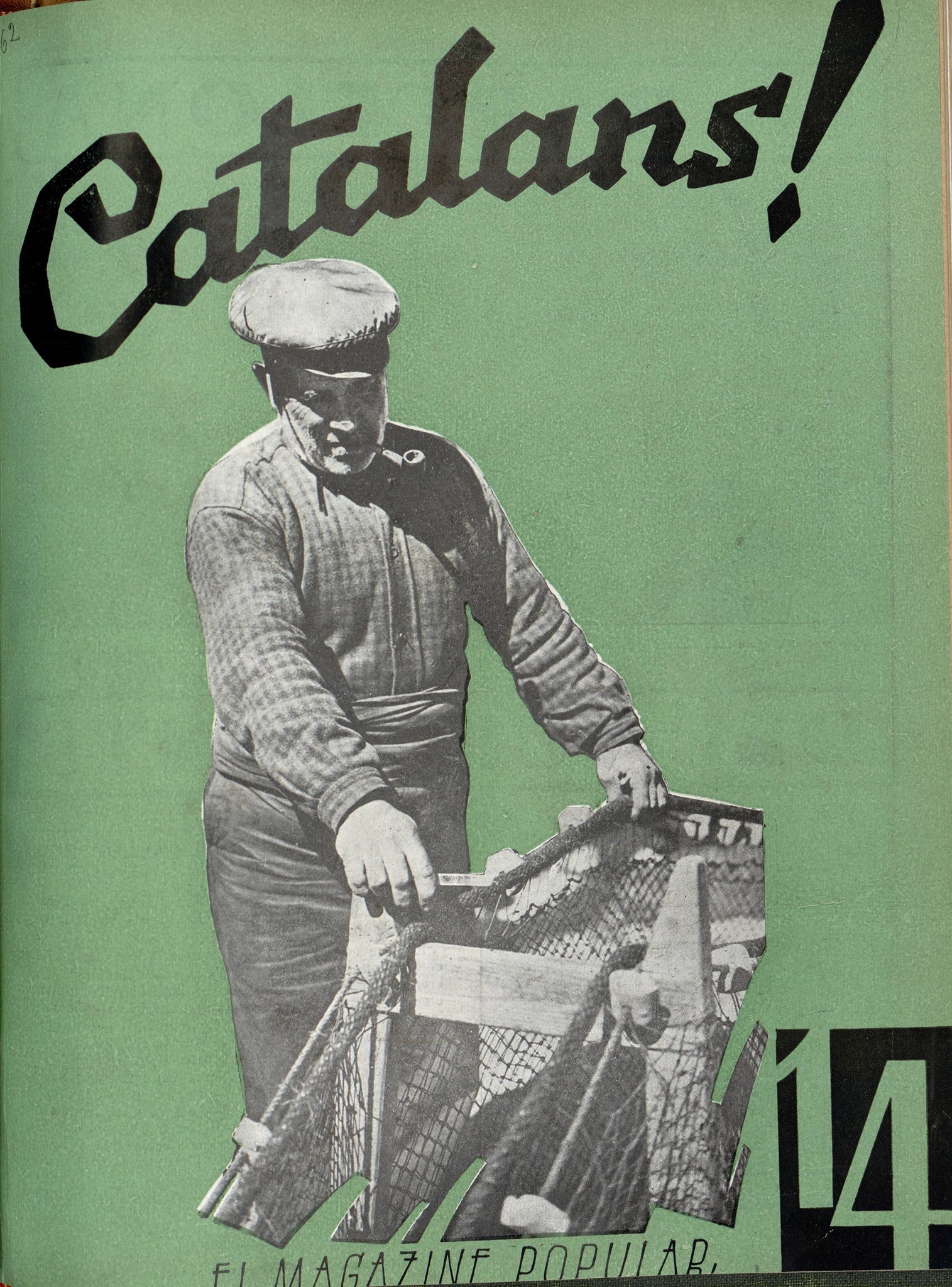

Catalans: el magazine popular, 30 June 1938.

These days nobody would dispute the fact that photography is a fundamental tool for the recreation of our recent history. Over recent years some photographers have been extolled in exhibitions, conferences, retrospective exhibitions, homages, publications and documentaries and they have been lauded as the official photographic chroniclers of our most recent past. Other photographers, despite having worked during the same period, and having dealt in their work with the same social issues and with the same intensity, have been forgotten.

In Catalonia, the polemical "Centelles" controversy" shook the photographic world and led to a re-evaluation amongst the general public of the importance of documentary images concerning the time of the Republic and the Civil War. But Agustí Centelles is not the only photographer who, on account of the war and Franco's ensuing repression, was forgotten about. In fact, there were many photojournalists who suffered the same fate, and it is precisely because of this that even today they are practically unheard of.

One of these photographers is Joan Andreu Puig Farran. Despite being one of the most active professional photojournalists in Barcelona during the 1930s, he is almost unknown.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Puig Farran was born in Belianes (Lleida) in 1904. As the 1920s drew to a close, and for reasons unknown, he and his family left Lleida for Barcelona.

His professional career became solidly established as a result of the work generated in Barcelona by the 1929 International Exposition. This event cemented the role of photojournalists in Barcelona, and marks a firm step forward towards the full modernity of the Republic period. Puig Farran went into business with his good friend Carlos Pérez de Rozas Masdeu. The new company, which focused mainly on portraiture, would have various names: “Fotografia Exposición. Pérez de Rozas & Puig” and “Art-Express”. The company was based at Rambla dels Estudis, 6, in the same building known popularly as the "Palace of News". They set up a photographic studio devoted to portraiture at the Exposition projection room where, in little more than a year they took almost 90,000 photographs. They charged 3 pesetas per photograph and the crème de la crème of the city sought them out to immortalise themselves.

PUIG FARRAN PHOTOJOURNALIST

With the installation of the Republic he separated from his business partner and started to work on his own as a photojournalist for newspapers and magazines. From then onwards, and until the end of the Civil War, it was customary to see photographs in the press credited to him. He formed part of a generation of photojournalists who were as unknown as they were important in the contemporary history of documentary photography in Catalonia. A generation that worked shoulder to shoulder to leave us a monumental legacy, a legacy that was published in dozens of national and international newspapers and magazines of the day. Centelles himself said in his private diary, “When I started to work on my own the following photographers were working in Barcelona: Merletti, Brangulí, Sagarra, Badosa, Pérez de Rozas, Torrents, Maymó and Puig Farran”.

Puig Farran's photojournalistic activities started at La Humanitat newspaper in 1931. Some of the most prominent photographers of the day also worked for this newspaper, such as Sánchez Català, Martí, Josep Domínguez, Gabriel Casas, Agustí Centelles and Josep Maria Sagarra.

Like most photojournalists of the time Puig Farran's work was broadly based. Reviewing his work for the newspaper we can see how he could photograph the facade of a new building for the Bank of Spain (13 February 1933, page 6), the death of Francesc Macià (26 December 1933, front page), injured gunmen (29 July 1934, front page) and the conversation between the president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys and Manuel Azaña at the Sant Hilari Sacalm spa (14 August 1934, front page).

.

In 1933 La Humanitat was acquired by the Llibertat S. A. publishing company which, two years later, would launch a ground-breaking and risky project, the evening newspaper Última Hora. It was an immediate success thanks to the spectacular front page, its typography and careful design, which left plenty of space for photographs and other graphic elements. The designer, brought straight from the United States where he was born, was the editor in chief, Josep Escuder, who encouraged young photographers such as Agustí Centelles, Antonio Goncer Rodríguez (Gonsanhi) and Joan Andreu Puig Farran. The large variety of topics that were the subject of photojournalists' attention during those frenetic times was practically inexhaustible, but what emerges from the events of the day is a clear tendency to concentrate on political events. The large number of photographs in newspapers and magazines was accompanied by a growing ideological element which became more radical as events unfolded.

From 1932 onwards Puig Farran started to publish photographs for La Vanguardia, the Catalan newspaper with the largest circulation. The Statute campaign of 1932, the anti-fascist demonstration of 29 April 1934, the events of October 1934 and the arrival of Companys in March 1936 are only some of the decisive events covered by photojournalists during this period. Photojournalists also covered sporting events for this newspaper, such as the football matches at Les Corts stadium (15 February 1934, page 4) and the skiing championships at La Molina (21 February 1934, page 2), amongst many other such events.

When the Civil War broke out Puig Farran was one of the first photojournalists to go to the Aragonese front. On 4 August 1936 L’Instant published some of his photographs with the following caption: “Conquest of Huesca. Captain Medrano's artillery fires over Siétamo.” Some days later we find him covering the Republican landing on Mallorca. His photographs were published in Última Hora on 22 August 1936 and in La Vanguardia the following day.

In August 1936 he applied to join the Professional Journalists Group (UGT), stating that he lived in Carrer Casp, 160 and that he worked for La Humanitat newspaper as a photojournalist paid "by the job". In January 1938 he was appointed spokesman for the management committee of the Barcelona branch of the photojournalists' section of this same organisation.

The growing demand for images and the availability of material for them determined photojournalists' daily work during times of war. The war marked a particularly prolific moment in Puig Farran's career. In fact, at that time he was one of the most important photographers working for La Vanguardia and many photographs were accompanied by a caption that read, “Photographs by Puig Farrán exclusively for La Vanguardia”. According to the documentation we have been able to uncover, his brother Alfons, who was also a photographer, helped him at that time.

During the Civil War photographic and cinematographic images became an instrument of propaganda of the first order. In addition to providing the media with photographs, photojournalists in Barcelona soon began to adapt their work to the needs of propaganda. This caused him pause for thought about his professional career, marked by a specific event on 3 October 1936 when the Generalitat de Catalunya established the Propaganda Commissariat, led by Jaume Miravitlles.

Photography adopted a leading role in books, posters, post cards, exhibitions and the Commissariat's own publications such as Nova Ibèria and the photo journal Visions de Guerra i Rereguarda as well as, from September 1937, the daily Comunicat de Premsa newspaper. Sometimes the photographs were the same as in other media, but on other occasions they commissioned specific projects and, quite often, the photographer was not credited.

The Commissariat had a photography department which included a section for photojournalists, with a dark room and copying facilities. The organisation's lack of an archive and the fact that the staff were not civil servants working for the Generalitat but were contracted according to the needs of the day, make it very difficult to determine the work of each photographer.

With regard to the Barcelona photographers it has been possible to establish the contributions made by Josep Brangulí, Gabriel Casas, Agustí Centelles and Miquel Agulló Padrós. Being able to consult the photographs in Joan Andreu Puig Farran's archive and compare them with the photographs in the Leica albums, which may be consulted at the National Archive of Catalonia, has enabled us to establish that Puig Farran played a leading role as a Commissariat photographer.

When the war was over, he was interned in various concentration camps, first in the south of France and from 1940 to 1943, at Miranda de Ebro. According to the historian, Josep Cruanyes, “In 1940, when some of the exiles were returned, he was interned in Miranda de Ebro, where he was sentenced to death”. He finally achieved freedom thanks to the intervention of his brother in law, Manuel Cases Lamolla, who was a commander in Franco's aviation. In 1945 he returned to Barcelona and two years later he married Samara Vicente.

As was the case with many other photographers, he refused to collaborate with the regime and resorted, in the end, to devoting himself to industrial photography and photography for advertising. Family records of the post-war period indicate his disappointment, a silence with regard to the past, and a deep resentment concerning the political situation.

Despite everything, Puig Farran continued to work for as long as he could. In 1952 he gave a new turn to his professional career and set up a company called Postales Color CYP together with the photographer, Antoni Campañà Bandrana. Together they produced the first collection of colour postcards in the whole of Spain and these formed the basis for the publication of more than 14 books for tourists.

Having retired, he devoted himself to a great passion of his, flowers. According to his family he would spend hours and hours tending his garden in Sant Vicenç de Montalt.

He died on 22 February 1982, at the age of 77.

Pablo González Morandi. Observatori de la Vida Quotidiana