My silences did not protect me, your silence will not protect you, 2011. Noelia Perez

It's not you, it's your theoretical framework.

Feminist meme

I

Over the last ten years many women photographers have become more visible in Spain and in Catalonia, or rather, there has been a growing interest in women photographers and their history. This growing interest in them, be they historical figures or currently active, has not been accompanied by an epistemological clarification of what we mean when we speak of 'woman', 'female photographer', 'gender', 'feminine' and 'feminist'.

As various female historians pointed out in the English-speaking world towards the end of the 1980s, when writing of women's history, too many things are taken as being tacitly understood, there being no 'woman' in the history because the category of 'woman' is a historical concept that is neither natural nor universal.

I think considering these questions now is supremely important in order to continue making progress in the question that interest us, namely, in progressing beyond the creation merely of histories of women photographers. That is the aim of this short, fragmentary and incomplete paper: to reformulate questions from a gender perspective as well as asking them historically. Thinking (and pondering) historically, as Josep Fontana said, helps to combat clichés and historical prejudices, which hinder an understanding of the world we live in.

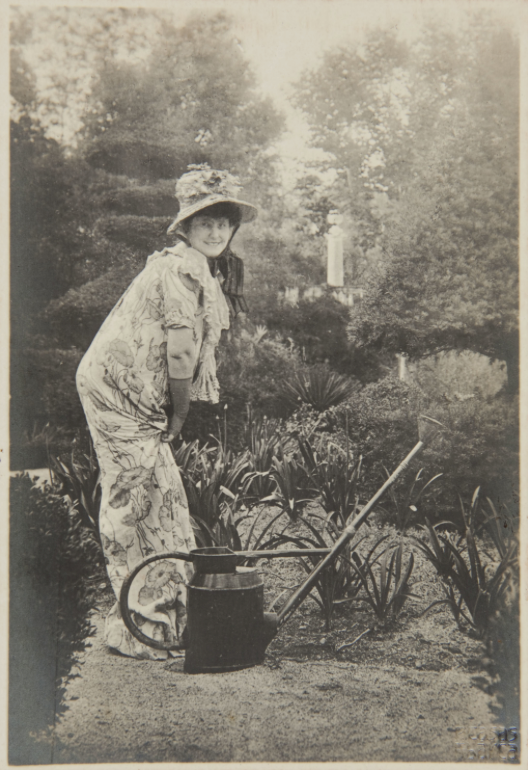

Untitled, circa 1900. Pere Casas Abarca

How can women's past, and gender relationships in the history of photography, be broached from the standpoint of the present day? What are the tools we need to explain ourselves in order to clear up these problematic questions? How can we put those tools to use? Historically, how have debates about gender difference in the history of photography been structured? What differences exist between the history of feminism and photography; feminism through the history of photography; the history of gender relationships in photography; the history of women photographers; the history of women photographers and histories with women photographers? Why do we speak of a feminine way of looking, but not of a masculine one? Why do we speak of women photographers, but not of men photographers? Why do we speak of history and not histories? Why do we not speak of the memoirs of women photographers? What does it mean to be a pioneering photographer? Or an amateur? Or a professional? Why do we consider Joana Biarnés to be the first Catalan woman photojournalist? Why are there no racialised women photographers in our histories of photography?

Female curiosity, 1970. Joana Biarnés

II

Joan Wallach Scott, one of the pioneering historians of women and gender, said that the history of feminism is the history of women who have only had paradoxes to offer since, historically, modern white, western feminism would certainly be a contradictory term in any attempt to obtain recognition of sexual difference, and would make it irrelevant. (0)

For Scott the concept of gender underlies the historical, social and culturally constructed character of sexual difference on which are based the changing meanings of femininity and masculinity in various historical contexts. Additionally, it provides a way of considering social relations. For Scott the history of gender raises the question of the importance of interconnections between different social relations, understood as unequal relationships and marked by imbalances of power, and by the negotiations around that power.

Following Scott, introducing the category of gender, in our case in the history of photography, is not to make a watertight compartment for a group of women, but to revise the whole discipline at every level, be it technical, historiographical or methodological. It implies, for example, studying what is meant by the so-called 'feminine way of looking' in specific historical contexts, and how it has been uncritically constructed. Leaving aside histories of women photographers to consider the history of gender relationships implies a complete change in the understanding of photography itself, its practice and its history.

A rephrasing as a question of the proposition in Scott's article might go something like, "Is the category of gender useful for the analysis of the history of photography?". Or is Barbara Christian's later rephrasing—"For whom are we doing a feminist history of photography?"—more useful? (1)

Portrait of woman and child, 1910-1920. Nissaga Napoleon

III

When we speak of feminisms we are talking about political cultures in which women, not only women, have taken a position regarding their subordinate situation and have demanded emancipation. But the woman spoken of in feminisms is not always the same woman. It depends on which feminists are speaking and their own context. That is why, when speaking of sexual difference, we must ask ourselves to what extent we are assimilating and accepting culturally constructed viewpoints and, when denouncing women's subordinate position with regard to sexual difference, we are contributing to perpetuating 'heterocapitalism', or whatever we want to call it. We must not forget that sexual difference is not an incontestable fact, but rather a cultural and historical construct that refers to something we call gender. Consequently gender is the cultural construct of sexual difference: there is no sexual difference without regard to gender.

With this in mind, all the alarm bells should sound when we see, time and time again, women photographers being equated with a so-called 'feminine viewpoint' and gender.

And it is precisely from this point of view that we can see the assimilation and acceptance of androcentric historical discourse in the history of photography. Men (photographers) are traditionally considered as the main subjects of a unique History, with a capital 'H', while, at the same time, they have been seen as beings without bodies, that is to say as subjects without regard to gender. This is why there is no history of photography that queries various issues concerning masculinity: if it is taken for granted that there is a 'feminine' viewpoint, why should there not be a 'masculine' viewpoint?

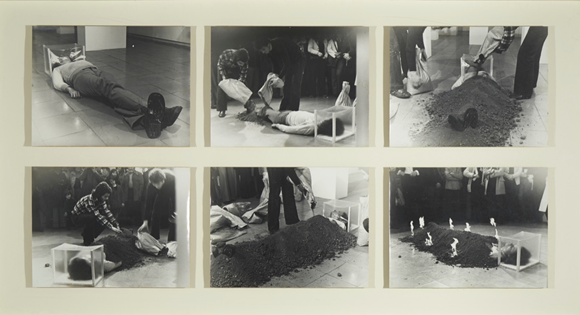

Relation of the four elements with man, 1975. Fina Miralles

IV

The history of photography is written from an androcentric point of view (2) and has overlooked outstanding women, androcentric hegemony failing to notice the viewpoint seen from the margins. Women, like other marginalised social groups that are disparaged, ethnicised, racialised and degraded, live on the margins of what is visible, and it is from these unrecognised margins that they have mostly played their role in history. Feminisms and their deconstructive tasks regarding sexual dichotomies (public, private, pacific, violent, feminine point of view...) have led to the questioning of commonly accepted norms of femininity conceived as being passive and peaceful.

What would happen if the main aim of photographic research were focused on drawing attention to the way in which femininity is constructed in a manner coherent with new capitalist and androcentric systems based on a consideration of women in front of and behind the camera? What would happen if we concentrated on the observation of a discursive construction of a counter-figure: the woman in front of or behind the camera who contravenes the hegemonic norms of gender by using violence against those who, in principle, it is her usual role to protect and care for? Where would we place her genealogically? What would be left of the 'female way of looking'?

My silences did not protect me, your silence will not protect you, 2011. Noelia Pérez

V

The history of women artists has, until a few years ago, been systematically ignored by official discourse. Gathering the threads of this forgotten history is not so much just a work of restoring memory as also questioning many of the fundamental conceptions, such as 'artistic genius', 'quality', 'school' and 'influence', on which the discipline of art history, and that of photography, rest.

Griselda Pollock brings together these new narratives in her Virtual Feminist Museum (3). In Pollock's museum "criticism works in a way that undermines (...) capitalist practice in cultural administration and rejects its essentialist, idealistic and nostalgic forms of museum and archive, which reproduce fascist, sexist and racist tendencies that can not be scrutinised or critically analysed since they are protected by a false notion of purity and aesthetic autonomy". (4) In this way the disruption of typical museum practice, focused on chronology, author, style and national school, makes it possible for the Virtual Feminist Museum to produce unthinkable alliances, relationships and liaisons between different kinds of objects and images to formulate questions and rescue unknown histories of women in front of and behind the camera.

If we applied Pollock's proposal in practice we would no longer be able to continue looking at 'sacrosanct' books on photography and their authors in the same way. From this perspective Gary Winogrand's Women are Beautiful could not be read without the resignification, made by his own daughter, Women are Beautiful Through the Eyes of a Chauvinist Pig, and the case is similar with Carrie Mae Weems' From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried. We can not refer only to Joan Colom's genius and the 'context of the period' concerning the photographs in Izas, rabizas y colipoterras without establishing a dialogue between it and The Waiting Game by Txema Salvans and the construction of the voyeur's androcentric gaze in contemporary photographic practice in Spain.

Chinatown, Barcelona, 1960. Joan Colom

A feminist conception of re-reading how the practice of recalling is understood, not only as a recovery of what has been forgotten (the mantra of the "forgotten photographs"), but also as an exercise in compilation. But not the compilation of objects or women who exhibit something 'feminine'. On the contrary, the museum, the archive and history understood in this way would be defined as a "critical laboratory" of feminist interventions based on montage and liaison that take constructed sexual difference as the main axis of the historical production of meaning.

VI

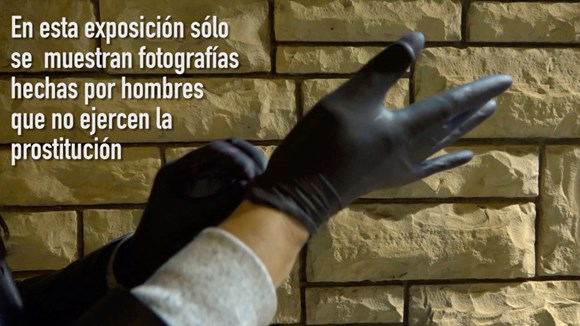

The 'Terrain Vague' exhibition, showing works by Txema Salvans and Joan Colom, opened on 20 April 2017 at the Juan Naranjo Gallery. In response to it an anonymous feminist group intervened in the exhibition with a video, which went viral on social networks, depicting the gallery being painted over.

The video documented the action with the following text:

"These photographers are considered to be the creators of the most important works concerning photography and prostitution ever made. This exhibition only shows photographs made by white, heterosexual cisgender men who are not themselves prostitutes. They portray sexual workers without their consent, and treat them as objects from a paternalistic point of view that is also one of morbid curiosity. This exhibition is not about photography and prostitution. It is the same shitty and hegemonic gaze as there ever was. Terrain Vague, we are watching you. #YoTambienSoyPutaPorqueyosoyquién elijecómorepresentarmiidentidad. [#ITooAmAProstituteBecauseIAmTheOneWhoDecidesHowToRepresentMyIdentity].

Without doubt, this kind of action is a shot across the bows indicating a new historical conception of photography and photographic practice in which theoretical positions are left behind in order to engage with performative and political action and, of course, new paradoxes.

Because history is always provisional and unfinished.

Capture taken from the video "We are watching".

(1)Joan Wallach Scott, Only paradoxes to offer. French feminists and the rights of man, Harvard University Press, USA, 1996.

(2)Judith M. Bennet, History Matters. Patriarchy and the Challenge of Feminism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Pennsylvania, 2006, (Conclusion: 'For Whom Are We doing Feminist History?', pp. 153-155.

(3)Amparo Moreno Sardá, El arquetipo viril protagonista de la historia, LaSal, Edicions de les Dones, Barcelona, 1986.

(4)Griselda Pollock, Encuentros en el Museo Feminista Virtual: tiempo, espacio y el archivo, Cátedra, Madrid, 2010.

(5)Pollock, G., Op.cit, p. 37.