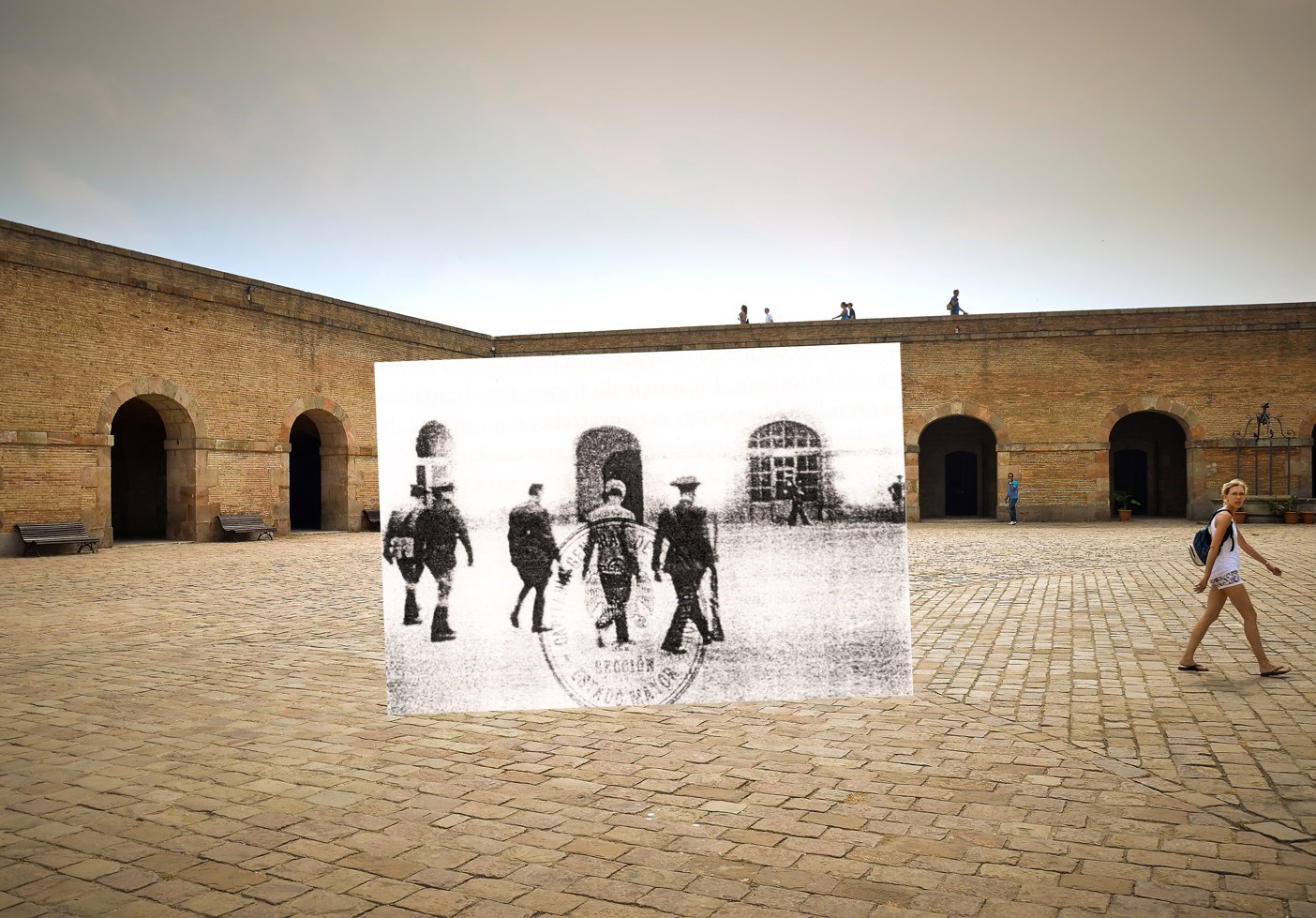

Parade ground at the Castle of Montjuïc. Barcelona, Ricard Martínez, 2011.

On 14 October 1940, Lluís Companys, president of the Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia) is led before a military tribunal. He was executed some hours later.

(Source: unidentified photographer, 1940 / Varela Archive, Cadiz).

Chaque époque rêve la suivante, la crée en rêvant.

Jules Michelet, Avenir, Avenir! 4 April, 1839

The rephotographic gesture.

We are what we observe. With every look we give a name to things and as we absorb them through our eyes they sculpt us from within. The product of such reciprocal contemplation results in the perpetual stratification of graphic registers. A vast visual archaeological site that invites observers to overlay the view of their predecessors with their own vision in a meticulous and obstinate activity called rephotography .

Rephotography basically consists of revisiting a historical image and taking a new photograph from the same standpoint. It is based on a scientific technique, used towards the end of the 19th century, to document long-term geological and ecological changes. It is an apparently simple procedure that involves a precise methodology and the taking of a photograph in a specific place at a specific time. Maybe because of this it gives rise to powerful concepts, imbuing the object with meaning and questioning the viewer. This is the force that has turned what was originally a photographic technique into a genre, making it an eloquent tool which can be used to create complex images, taken at different times, and project them onto the future, propelled by the gravitational force of our ancestors' dreams. This article reviews some aspects raised by photography and considers the motivations behind the photographer's work by means of a fruitful peregrination between the archives, where the photographs are kept, and the places where, once, they were taken.

Repression and resistance. Photographic installation in the Plaça de la Catedral, Barcelona. Ricard Martínez, 2010.

Francisco Franco and Josep M. de Porcioles, mayor of Barcelona, after the compulsory visit to the cathedral during one of the dictator's last visits to the city. (Source: Pérez de Rozas, 1970 / Photographic Archive of Barcelona.)

Old glaciers and deserts

The German mathematician Sebastian Finsterwalder established the first principles of repeat photography when, in 1888, he embarked on a study of the glaciers in the Bavarian alps. The methodology was based on photogrammetry, the technique for measuring the dimensions and location of objects with the help of photography. The research therefore involved setting up a series of photographic stations from which to regularly photograph the glaciers in order to study any changes or fluctuations in these colossal and fragile rivers of ice.

Repeat photography soon became an important procedure for producing rigorous and complex images suitable for use in the scientific study of geological and ecological changes to the landscape. In the United States of America, research into the arid landscape of the southwest often used contemporary photographs to compare with photographs and drawings that had been made previously by artists and photographers involved in the scientific expeditions organised by the Federal Government during the 1870s. By the 1940s this technique was a common procedure in this kind of study in both Europe and America.

An immense resource

Towards the end of the 1970s two notable photographers, Mark Klett and Camilo José Vergara, took this methodological technique up again to adapt it more closely to a photographic discourse capable of providing new content.

Mark Klett trained as a geologist, which explains the capacity of his work to transmit the passage of time so powerfully and provides a clue about how repeat photography became a tool for creative work. Klett's work has its origins in the New Topographics movement, which was concerned to represent human impact on the landscape, and Klett's main focus was on the interaction of time and the subject within landscape. In 1984 he published Second View. This was the result of a huge project that began in 1977, the Rephotographic Survey Project, which consisted of photographing again the landscapes of the American Northwest that had been photographed during the 19th century as part of the previously mentioned political and scientific expeditions commissioned by the US Federal Government. He took up this task again in 1990, publishing Third Views, Second Sights, in which he assembled the photographs taken in the 19th century, the ones taken in the 1970s and the ones taken towards the end of the 20th century. His extensive work encompasses the images taken by explorers in what was still a wild environment. When photography returned to these scenes they were by then part of consolidated States forming part of an important country. When, years later, he returned, the changes were verified through the camera lens with new digital formats and, most importantly, through the photographer who had grown older too. His complex images constitute a new topography in which the political reading of a landscape is combined with a profoundly intimate and geological perspective.

Camilo José Vergara is a sociologist and his work centres on how environmental influences affect social behaviour. In the 1970s he began to adapt sociological methodologies to his own systematic work. Since then he has photographed the most dilapidated districts of the large US cities, in a kind of transhumance of photographic vision. He made a way of working a life-long project and has turned his works into an archive which is a visual encyclopaedia of suburban North America. The photographs he has organised and preserved show how these districts have been eroded by time, as well as depicting the socioeconomic factors at play. These important photographs have been published in various books and audiovisual projects. Some of them can be seen online from his Tracking Time website. The photographs are related to each other and with the landscape in a complex interactive structure. Vergara is considered to be the builder of virtual cities made with photographs that reveal the form and meaning of neglected urban communities.

Lots of love to do. Photographic installation in the Plaça Reial, Barcelona. Ricard Martínez, 2017.

Photomontage with various pho-tographs of the first demonstration for LGTBI rights.

(Source: unidentified photographer, 1977. Photographic Archive of Barcelona / Diari de Barcelona collection.

Isabel Steva Colita. 1977.

Gabriel Casas i Galobardes, 1923-1935. National Archive of Catalonia.

Pepe Encinas, 1977.

Xavi Mestre, 1977.

Perez de Rozas, 1977 / Photographic Archive of Barcelona).

The cultural viewpoint

Works such as those by Klett and Vergara open the door to learning about a new world which, at the same time, is old and unfinished, inhabited by photographs and repeat photographs, dynamic visual objects that act as a reagent to generate strong connections between both themselves and the viewer. The flow of images is so dense that, often, it is possible to connect them as images taken from the same standpoint at different moments in time. This is due to the great frequency with which certain places have been graced with the photographer's attention and the prominence of a cultural influence that encompasses the visual education of the viewer. Corinne Vionnet's work is an example in this regard since it reveals this cultural influence by superimposing numerous views of well-known monuments taken from social networks on the Internet. These then, once more, become images broadly reminiscent of painting.

The current enthusiasm for inherited images, together with meticulous composed images derived from rephotography, make it possible to distinguish two strands of rephotography: (re)connected images and (re)visited images. These images constitute obstinate landscapes which imbue each vision with importance. Furthermore, they fill a methodology, rephotography, developed, as has been mentioned, in the 19th century as a scientific aid, with cultural content, so that in the 20th century it became an aid to creation as well.

The visual projects which use rephotography are absolutely heterogeneous, nevertheless, they have their origins in a premise which is apparently as rigorous as the fact of repeating a pre-existing photograph from the same place. They often reveal the modern concerns of the earlier photographs and announce those of the future, sleeping in the dreams of the present, making evident the greater or lesser invention contained in the new works. Because it is precisely then, when everything seems the same, that it becomes clear that the images are different. Sometimes, photographs which are apparently so similar, taken by people separated in time, are indications of the changes that have taken place behind the camera, to the photographers and, above all, to the viewers who see everything. The work of Douglas Levere is a good example in this regard. Consider Changing New York, the book published by Berenice Abbott in 1939 about the great American metropolis. In 2004 Levere published New York Changing with the same camera and exactly the same viewpoint. The photographs are so similar that sometimes even in the shadows coincide. That is because the photographs are not only taken at the same time, but also at the same time of year. It has to be remembered that the sun travels through the sky from east to west but also travels from north to south with the change of season. When Levere photographs of the same landscape as Abbott with the same light, not only is there a new photographer occupying the same place where another has been previously, but from a sidereal perspective, the planet and its star are also in the same place. Levere became a miniscule, and patient, tamer of the planets. Rephotography as a cosmic gesture, nurtured by the epic achievement of living.

Rephotography is, essentially, the search for a point of view, a precise place which, nevertheless, is constantly moving, propelled by an unstoppable entropy towards the future. Shortly beforehand, in the same place, there was the lens of another camera. Behind that lens was a photographer. To find the viewpoint is to step somewhere where someone once stepped before and it is, therefore, a gesture of intergenerational empathy in which rephotography is the subsidiary product, evidence that someone was once at the same place from where now there is another gesture, another landscape.

The corporal view

The photographs acquire an extraordinary force and become unusually loquacious. They provide precise information about the scene represented. Thanks to this, the viewer can precisely reconstruct location of all the people and elements that appear in the image. From this powerful viewpoint the observers gaze can encompass two times: the past, as represented in the photograph, and the future occupied by the viewer. The experience produces the sensation of being able to access the facts represented in the image.

This illusion can, however, be unmasked with such a simple and forthright strategy as placing large scale photographs at the place where they were taken. It is a simple gesture that unleashes powerful sensations. In the face of such large images the eyes are not enough and they need the collaboration of the whole anatomy to be observed. They are photographs that must be observed with the feet. In addition to this interaction the photograph also mutates into sculpture, shedding its two-dimensionality to form part of its three-dimensional surroundings as the image itself blends with its environment in a new, temporal, artifice. It is true that the viewer may have the fleeting impression of participating in the historical events portrayed, but this sensation is more readily verified in a different way, as the illusion reveals and gives importance to the viewer's own gaze. As this gaze surveys the image the eyes move between the real view, in front of them, and the representation. The historical image and its environment together become a temporal map that requires the viewer to adopt a position with regard to what is being viewed. This displacement distances viewers from their centrality in time enabling them, in this way, to perceive beyond the moment in which it has befallen them to live.

This corporal vision therefore reveals the need to exercise a critical attitude towards the environment. Precisely, the fact of being able to wander between the different images subverts the flat image, the object of the ploy, enabling viewers to reflect on their wanderings, the erratic trajectory that has brought them occupy and depart from this point of view.

Rephotography leads viewers to walk within the dreams of their forebears, who sketch an outline of what they wanted to be, making us think of the longings will leave behind for others who succeed us to revisit.