Josep Maria Roset, photographer

When I saw Josep Maria Roset's contact prints I knew immediately that I was looking at an exceptional case. After the impact of the first impression I wondered, as you often do when faced with an interesting and coherent body of work, who had chosen these photographs, because all of them were so good. It is not so easy to discern such a forceful character by delving through negatives in an archive. Recently we have become accustomed to this kind of recovery, but in most cases what emerges in the present is a nostalgic feeling about the material that sates our curiosity about the past through the mere documentation of history and customs. Given the content and scope of his archive, so closely linked to his city and district, such a discovery is, in the case of Roset a rich seam indeed. However, Roset's photographic work is not a local archive, rather it constitutes a body of work in which each photograph conjures up a universal interest in the history of photography, which we know is History with a capital letter, one that concerns everything to do with modern human existence. Roset's work deals with these crucial issues during the second half of the 20th century, issues that have drawn the attention of good photographers, and that is why he can be associated with the main stylistic movements of photography in our country. We have yet to mention, however, that the criteria for the selection are those of the photographer himself, and that it was he who chose the photographs that would be proposed for his first book. This makes it possible not only to recover his photographs, but also his voice and his intentions. Something else needs to be mentioned. Are there more photographs like these or do these hundreds of masterpieces constitute the whole? The answer is astonishing because Roset's archive constitutes one of the most enormous personal legacies in Catalan photography. Roset, who is still active at the age of 82, has bequeathed us an archive that it contains almost 350,000 negatives.

Learning of the size and quality of an archive such as Josep Maria Roset's after many years of research in the period produces a strange sensation. This photographer, winner of the Trofeu Egara and Negtor prizes in 1970, had remained on the margins with regard to other photographers vying for awards at the time, his work, for all practical purposes, having disappeared from retrospective exhibitions and general works on Catalan photography. But today his work reveals its true importance. He is the best photojournalist of the 1960s, taking his rightful place alongside such great photographers as Paco Ontañón and Ramón Masats, and the intimate, humanistic photographers Gabriel Cualladó and Ricard Terré, amongst others. His introspective portraits of personalities from the worlds of culture and theatre have the same outstanding quality as the best portraits produced by Schommer, Juan Dolcet and Pomés, and his photographs are on a par with the austere and symbolic landscapes of Paco Gómez, as well as with the grace and social satire that we know in the work of Maspons and Colita, with their insolent, bold and scathing criticism of the dictatorial system as the restoration of democracy approached. And they are on par also with the photographs of street scenes during the transition to democracy that fill the archives of the staff photographers who worked as photojournalists for the magazines of the day. Furthermore, his photographs also display the metaphoric power of the surrealism of the 1980s. Once we become familiar with his work it becomes incumbent on us to make a wholesale reappraisal of the main figures and achievements of Catalan photography at that time.

When I saw Josep Maria Roset's contact prints I knew immediately that I was looking at an exceptional case. After the impact of the first impression I wondered, as you often do when faced with an interesting and coherent body of work, who had chosen these photographs, because all of them were so good. It is not so easy to discern such a forceful character by delving through negatives in an archive. Recently we have become accustomed to this kind of recovery, but in most cases what emerges in the present is a nostalgic feeling about the material that sates our curiosity about the past through the mere documentation of history and customs. Given the content and scope of his archive, so closely linked to his city and district, such a discovery is, in the case of Roset a rich seam indeed. However, Roset's photographic work is not a local archive, rather it constitutes a body of work in which each photograph conjures up a universal interest in the history of photography, which we know is History with a capital letter, one that concerns everything to do with modern human existence. Roset's work deals with these crucial issues during the second half of the 20th century, issues that have drawn the attention of good photographers, and that is why he can be associated with the main stylistic movements of photography in our country. We have yet to mention, however, that the criteria for the selection are those of the photographer himself, and that it was he who chose the photographs that would be proposed for his first book. This makes it possible not only to recover his photographs, but also his voice and his intentions. Something else needs to be mentioned. Are there more photographs like these or do these hundreds of masterpieces constitute the whole? The answer is astonishing because Roset's archive constitutes one of the most enormous personal legacies in Catalan photography. Roset, who is still active at the age of 82, has bequeathed us an archive that it contains almost 350,000 negatives.

Learning of the size and quality of an archive such as Josep Maria Roset's after many years of research in the period produces a strange sensation. This photographer, winner of the Trofeu Egara and Negtor prizes in 1970, had remained on the margins with regard to other photographers vying for awards at the time, his work, for all practical purposes, having disappeared from retrospective exhibitions and general works on Catalan photography. But today his work reveals its true importance. He is the best photojournalist of the 1960s, taking his rightful place alongside such great photographers as Paco Ontañón and Ramón Masats, and the intimate, humanistic photographers Gabriel Cualladó and Ricard Terré, amongst others. His introspective portraits of personalities from the worlds of culture and theatre have the same outstanding quality as the best portraits produced by Schommer, Juan Dolcet and Pomés, and his photographs are on a par with the austere and symbolic landscapes of Paco Gómez, as well as with the grace and social satire that we know in the work of Maspons and Colita, with their insolent, bold and scathing criticism of the dictatorial system as the restoration of democracy approached. And they are on par also with the photographs of street scenes during the transition to democracy that fill the archives of the staff photographers who worked as photojournalists for the magazines of the day. Furthermore, his photographs also display the metaphoric power of the surrealism of the 1980s. Once we become familiar with his work it becomes incumbent on us to make a wholesale reappraisal of the main figures and achievements of Catalan photography at that time.

Where was this photographer? Why do we not know and why can we not name his evident triumphs? Roset worked as a photographer for almost two years at the recently-created agency, Europa Press (1959-1960), for which he provided major photographic reports, one of which was published by Life magazine. He produced a magnificent front covers for Arriba, photographic reports for La Actualidad Española, and he was a theatre portrait photographer, amongst other photographic assignments. But the vicissitudes of life led him to stay in Rubí, documenting the life of his contemporaries and of those passing through the town. Roset has a reporter's instinct and an ability to highlight the inherent interest of his subject matter in a way that few photographers can equal.

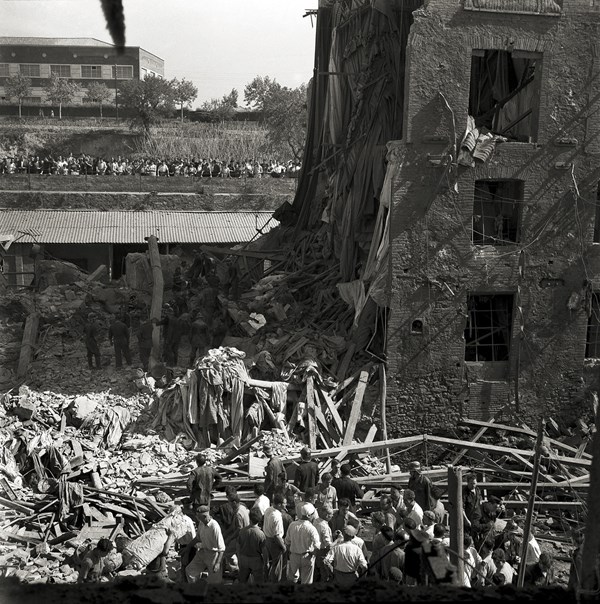

Explosió a Can Viloca, 1958, Josep Maria Roset

Explosió a Can Viloca, 1958, Josep Maria Roset

This book is but a foretaste of Roset's work and in it the works and the photographer's personality meld together seamlessly.

The press photographs for the Europa Press agency have a very personal character with bold, well-framed foregrounds, a skill non too common amongst the photographers of the day. He takes advantage of elements in the surroundings to express aspects of the settings around him that cannot be expressed in a text. Over the course of two years Roset proved himself to be a very good photojournalist. But his professional career was cut drastically short on account of the hounding he received from Franco's secret police. In search of liberty he left for France. If such a move had been easier for Spanish immigrants in the 1960s, Roset would perhaps now be a Koudelka, who is to say? The son of a goatherd, like Miguel Hernández in poetry, he had a photographer's instinct that he expressed through an unfettered, direct style that was faithful to the truth in a way that showed his free spirit, a spirit as free as the poor were allowed to be.

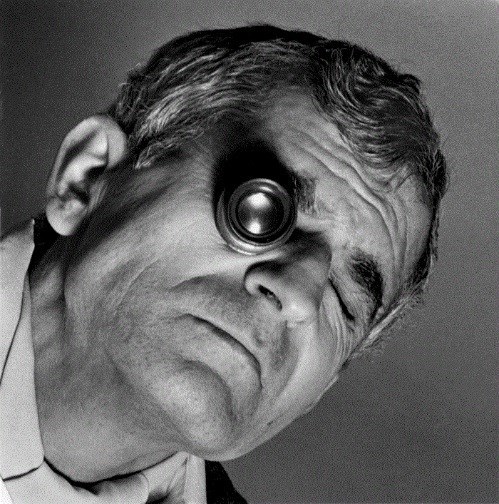

Roset's portraits display a strange melancholy. His subjects almost never look at the camera. They are lost in thought, self-absorbed and reluctant to express what is happening to them. Their humanity rises above commonly-held social clichés. Roset likes the rigid, hierarchical poses of statues, dilapidated and often dangerous ruinous houses, abandoned lofts, and that is why he photographs his subjects in settings containing statues or through doors and windows through which they emerge in the flesh as anonymous heroes. He does not rely on complicated perspective, sometimes employing uncompromising minimalist foregrounds to express all the drama of a life. Such is the case with the Nazi war criminal Otto Skorzeny, whose mere glance he could not tolerate. Rather he shows the scars that turn what would have been a photojournalistic portrait into the police photograph that it would have been necessary to take on the day of his detention. This is how Roset felt, and we see him shooting his camera as if it were a gun, with the accuracy and determination of a member of the maquis in the mountains.

When Roset returned to his hometown he placed his observational talents at the service of the people and set about recording daily events. But what daily events they were! How strange everything seems in the daily life presented to us in his photographs. In them, not only does he show what is happening in the photograph itself, he also describes the people portrayed and what they signified at that moment. But this is something we do not see in the photographs, rather we see a harsh world, sometimes cruel, absurd, full of signs. Sheep hanging or stabbed, a ball of stone hanging over an abyss, a couple lost in the middle of nowhere, politicians cutting the tape on a road that leads to the end of the world. It is the narrow, suffocating and sad world of the final years of the Franco regime and the first street protests of the Transition years. Roset's photographs are those of a witness to what he saw before his own eyes, remarkable shots of workers' struggles and political meetings. Some of the faces we see are still known to us, some of them are now high-ranking politicians, but here they are, as with the portraits, set in a shroud of melancholy. Roset sees all of them with the incredulity of someone who has seen a great deal, who sees deeply, someone who has not changed sides in all his life and who continues to see things from the same position a libertarian worker would have.

There is an aspect to Roset's work that avoids pessimism, scepticism and cold documentary distance. It is an intimate aspect, beside his family and friends, that allows him to make a little fun of himself and to set the scene, something he learnt from the actors he mixed with when he was a theatre photographer. His tenderness and the gentle care with which he approaches children and his wife show his wisdom about life. Like a universal timekeeper with a well-focused lens he applies himself to feelings, and life's dramas, from a newborn baby's first breath to the old age, full of joy, of a woman whose name he still remembers, Balbina. All his subjects have been important in his life, or so it seems. An important aspect of his work concerns young people, adolescents, full of curiosity and energy. Roset's intimate photography is the storyboard of a film we would like to see about ourselves, in the style of Nouvelle Vague, more than Neorealism, without imposing on ourselves the foreign, distant and stereotyped models of the mid-twentieth century that we lived through so peculiarly, torn from the land and forced through the factory gate, stripped of freedom of thought and forced to observe the ideology of the raised hand salute. Roset's work represents the slow movement of rising up and returning.

That is why it is so urgent to fill the gaps in the history of photography, a history that has ignored such an outstanding photographer as this and one who is of crucial importance for any understanding of the importance of the photographic art in Catalonia and its standing in the world. I would like to quote the words of Gabriel Querol, another of those passed over in our photographic literature, upon seeing the contact prints, "I became aware that Roset had the quiet intensity of a first-class mind, a very particular way of looking at things and at life, and with a certain confidential predisposition towards the unusual and expressive that gives substance to what we know as the audiovisual world".[1]

Laura Terré

Historian of photography and exhibition curator

Text by Laura Terré published in Tal com jo ho he vist. Fotografies de Josep Maria Roset. Rubí, September, 2014.

[1] Gabriel Querol Anglada. José Maria Roset. Premio Negtor 70 de Fotografía, in A Imagen y Sonido, No. 38, August 1971